Indore Tragedy: Clean Image, Dirty Water, Shameless Politics

Death drips from the tap, abuse from the tongue

If the Indore tragedy is viewed merely as an official news report, it can be summed up in a few lines: contaminated water, over a dozen deaths, hundreds taken ill, a minister’s abusive remark, followed by a routine apology.

Deaths caused by polluted tap water in Indore’s Bhagirathpura area, dozens of hospital admissions, and the cold, bureaucratic tone of official statements together form the first layer of this story. But anyone familiar with India knows such incidents are never so simple. This tragedy reflects a deeper mindset that has thrived for years in the corridors of power—where political ego and image management take precedence over human life.

The dirty water flowing from Indore’s taps has become a metaphor for the political, administrative, and moral decay concealed beneath glossy slogans, publicity campaigns, and national awards. Ironically, this is the same city repeatedly celebrated as India’s “cleanest city.”

In Indian politics, leaders often live two parallel lives. One appears during election rallies, on hoardings, and in scripted speeches, where every leader claims to be a servant of the people and a champion of the poor. The other emerges the moment an uncomfortable question pierces their carefully protected comfort zone.

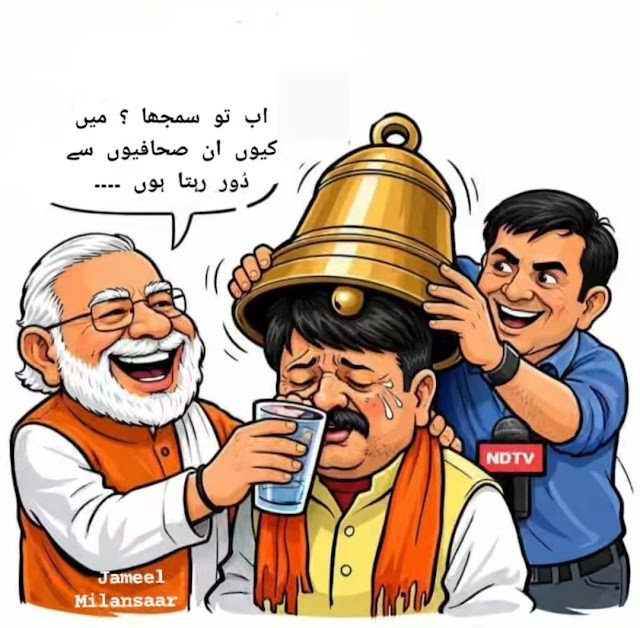

During the Indore water-supply crisis, when a journalist questioned the state Urban Development Minister and local MLA about accountability, compensation, and permanent access to clean drinking water, the response was dismissive. The minister branded the query a “free question” and followed it with an offensive remark—exposing an entrenched sense of superiority.

The irritation, authoritarian arrogance, and moral bankruptcy displayed in that moment revealed the politician’s real persona. The instinct to humiliate a questioner rather than answer responsibly reflects a troubling trend within Indian democracy.

Indore’s repeated branding as a clean city had turned it into a national “model.” Promotional images showed spotless roads and invisible drains, while officials touted its waste-management and “zero-waste city” credentials as exemplary.

Yet the real filth often lies where cameras never reach—inside pipelines, sewer systems, and government departments weighed down by years of corruption, negligence, and patronage. In Bhagirathpura, leakage in a main pipeline running beneath toilets allowed sewage-contaminated water to enter household taps, exposing the failure of aging infrastructure.

Official records fluctuated on the death toll—sometimes four, sometimes seven, sometimes eight to ten. But in poor neighbourhoods, deaths are not mere numbers. Each loss represents a family shattered, a livelihood destroyed, and a future erased.

Against this backdrop, as the minister returned from visiting the affected area, a journalist asked questions that should be routine in any functioning democracy: Why were private hospital bills not reimbursed? When would families receive compensation? What concrete reforms were planned to ensure safe drinking water?

The questions were neither hostile nor personal. Yet the minister dismissed them with contempt. Television cameras captured not only the abusive language, but also the indifference usually concealed behind rehearsed statements and official smiles.

As expected, a standard apology followed—fatigue, stress, grief, regret if sentiments were hurt. But the issue is not the words; it is the attitude. What emerges in anger often reflects deeply held beliefs. Even after the apology, the question remains: does the minister consider such questions legitimate, or still “free” and worthless?

For the opposition, the incident became political ammunition. State Congress leaders circulated the video on social media, cited higher casualty figures, and demanded the minister’s resignation, accusing the government of negligence and arrogance.

India’s political history offers few examples of resignations on moral grounds, making such demands largely symbolic. Still, a fundamental question persists: does a minister retain moral authority when people die from tap water under his watch and accountability is replaced with hostility toward the media?

At the administrative level, emergency responses were announced, investigations ordered, and patient statistics released—three deaths here, four there, over 150 patients treated, dozens discharged. On paper, the response appeared adequate.

But statistics cannot carry the weight of human suffering. Behind every number lies a traumatised family, unpaid hospital bills, lost income, and lingering fear.

Though centred on Indore, this is not just a local story. It reflects a national contradiction—of a country that worships rivers and calls the Ganga a mother, yet allows drinking water to become lethal, even as slogans of “Clean India” continue to echo.

From a journalistic standpoint, the episode sends a disturbing message. When a minister dismisses a question as “free,” it signals not just contempt for one reporter, but an attempt to define which questions are acceptable. Only questions that preserve image and avoid failure are welcome; the rest are labelled nuisance or agenda.

If journalism accepts this standard, the line between news and advertisement will disappear. The “fault” of the Indore reporter was simply that he spoke in the language of reality, not publicity.

The Indore tragedy underscores a harsh truth: in today’s democracy, the cheapest commodity is the life of the common citizen, while the most valuable is the ego of those in power. A few condolences, a handful of announcements, and the system moves on—while affected families carry the burden for years.

The polluted water flowing from Indore’s taps is not just a civic failure; it is a mirror held up to the democratic system itself. More disturbing than a minister’s abuse is the collective apathy that allows deaths to be forgotten, while offensive language becomes the only scandal.

Perhaps one day the nation will move beyond demanding resignations and demand structural reform—where access to clean drinking water is not treated as a favour or a fragile hope. Until then, incidents like Indore will remain both headlines and silent stains on the national conscience—stains that neither advertisements nor apologies can erase.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the organisation.

By Jameel Ahmed Malansar

Mobile: 9845498354

Source: Haqeeqat Time